Bridging the UK's Skills Gap: How to win in a skills crisis AND avoid overspending on recruitment with Rebecca George CBE

Tuesday 9th April

TA Disruptors is back for a second season. And we promise you, it was worth the wait.

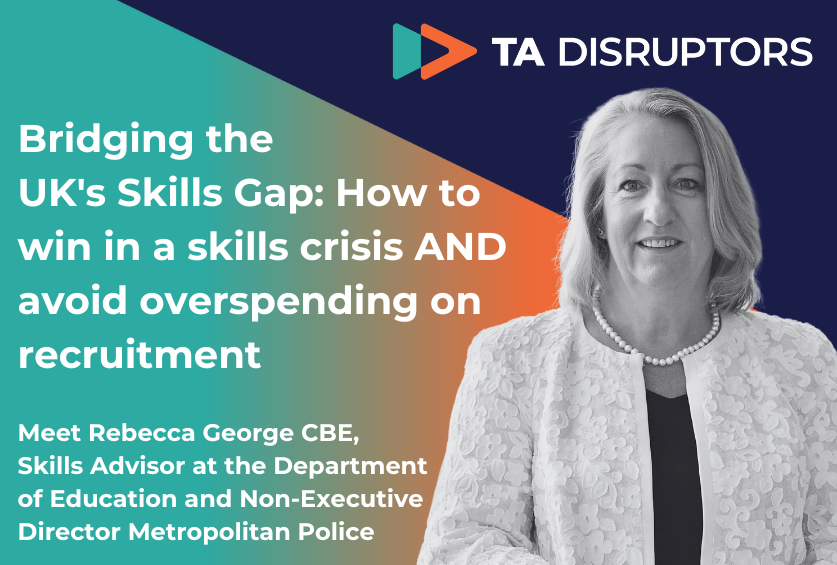

For our first episode in this season on skills based hiring, Robert Newry is joined by Rebecca George CBE.

Rebecca is one of the UK’s leading experts on skills, serving as the Skills Advisor at the Department for Education and a Non-Executive Director at the Metropolitan Police. With twenty years at IBM and nearly fifteen years at Deloitte under her belt, Rebecca is a staunch supporter of skills reform –– her insights into the skills shortage, inter-employer partnerships, and the necessity of innovation to address talent scarcity in our pipelines are crucial messages for all talent acquisition teams to consider.

Whether you want a deep dive into skills-based hiring, upskilling, or cutting-edge insights from a disruptor who balances innovation with pragmatism, this episode is a must-watch.

Join Rebecca and Robert Newry for episode one of Season two of the TA Disruptors podcast as they discuss…

💡 How the UK Government is thinking about skills reform, why we’re actually in the skills crisis, and why collaboration between the education system and employers –– focusing on skills not vacancies –– is vital for unlocking economic growth

📉 Why our future workforce needs diverse capabilities that blend technical skills with versatility, and how failing to select for or nurture this unique skillset means the UK risks lagging further behind

👀 Why employers might be thinking too narrowly about the skills they need for future growth, and how to reframe your thinking around talent acquisition, skill development, and succession planning

💥 Why scrapping the CV and hiring for potential is the key to opening up alternative talent pools and plugging skills deficits; the rigorous assessment process required to enable this shift; and the consequence of not doing so on social mobility

🔥Why using AI to look for people with a 100% skills match and simply reinforce the process you have today could lead to failure, and what to do instead

⏭️ What does it really mean to be a skills-based organisation really mean and are we really doing enough to upskill our employees?

We promise it will be the most valuable podcast you listen to this week.

Listen to the episode here 👇

Podcast Transcript:

Robert: Welcome to the TA Disruptors podcast. I'm Robert Newry, CEO and co-founder of Arctic Shores, the task-based psychometric assessment company that helps organisations uncover potential and see more in people.

We live in a time of great change and TA disruptors who survive and thrive will be the ones who learn to adapt and iterate and to help them on that journey. In this podcast, I am speaking with some of the best thought leaders and pioneers who are leading that change.

In this second series of the podcast, I'm focusing on skills-based hiring. And I'm very excited and thrilled to be welcoming Rebecca George, CBE, skills advisor to the Department of Education and non-executive director of the Metropolitan Police.

Rebecca has defined her career by digital transformation and leveraging data. She worked for nearly 20 years for IBM, travelling all around the world with them, and then nearly 15 years with Deloitte, ending up as a managing partner, and is also a past president of the British Computer Society.

Not a typical career, one would have thought, for a woman who studied English language and literature at the University of Oxford in the 1980s. But you've now turned your energies to supporting the public sector and your passion for skills reform. Welcome to the podcast, Rebecca.

Rebecca: Thank you very much. It's lovely to be here.

Robert: So talking about skills and as somebody who leads and advises on skills.

I think we often hear and talk about the skills crisis. And this is clearly a big challenge for many organisations in the UK and as well around the world. And for me, it falls down to two big challenges around this. First is, we simply don't have enough skills, digital skills that organisations need as we sort of go through this great transformation and digitisation. And secondly, we haven't really figured out we train and acquire more of those skills. I would love to hear your perspective on the skills crisis and where we're at and why we're at this point.

Rebecca: Thanks very much. That is a huge question to start with and we'll unpack it a bit.

So when I talk about skills I'm really focusing on sort of technical and vocational skills. The sorts of skills that are developed by education sector. And one of the, I think one of the reasons that we're in the crisis we're in is because our further education sector has been underinvested and undervalued for about 40 years. 50% of the population who don't go to university go through further education and many of them are acquiring the kinds of technical and vocational skills that we need for future growth for the country.

But virtually nobody seems to actually understand what goes on in that sector. When you walk in through the door, it's amazing, by the way. We might come back to that a bit later on. So the further education sector hasn't really developed the numbers of people that we're looking for. And because employers haven't been really involved in the discussions around the courses that are offered.

Quite often the types of qualifications people have been coming out with haven't been exactly what employers look for. The skills reform that the government is engaged in at the moment, which has been going for three years and is a 10-year plan, is designed to put employers right at the heart of the skills reform. Get employers involved with what they really need, not what vacancies you have today, but what skills you really need for the future.

The other part of this crisis is, as you said in your introduction, the world's changing. The skills we need are entirely different. If you look at what we need for the green agenda and digital transformation, which we need across all sectors.

We need people with different capabilities. They may have a route in the same sorts of technical skills, but actually they need to be able to do things differently. And quite often we need people with a fusion of skills that come across different disciplines, rather than just being able to do one thing. So we have a massive shortage of the kinds of people we need to build the UK for the future. If you're thinking about energy, utilities, power, nuclear, green, digital, life sciences. We have a deficit of skills in all of those areas. And actually, in some in some of those areas, we just don't we know that we just literally cannot train enough people to fill the deficit. And unless we find a way of doing that, the UK is just going to fall further and further behind.

Robert: I think that's fascinating that, you know, we, you know, as you articulate there, we've got this big gap and this big problem and we, and many organisations seem to recognise it. There are clearly some ways to solve that that's sitting in front of our eyes and I think part of what you shared there that is interesting is there's clearly been an obsession with university and graduate level recruitment and as a source of talent for training up people. And yet we've got this whole other area that we've overlooked and hasn't really had the same public credibility or even promotion that universities have.

Do you think then that the simple answer to this is just that, oh, we need to go to the further education sector now, rather than be obsessed with university education? Or is there actually, you alluded to a little bit about that, that we hadn't, the further education sector hadn't quite brought out the skills that people were looking for.

So there's a little bit of, we need to do a bit of reform in the skills. And I'd like to explore a little bit that fusion point, but let's start with what are the skills that are coming out of further education? Have they changed? And is that therefore something that companies should be looking much harder at as a source of talent?

Rebecca: Yes, so definitely. The people that are coming out of the further education system now are much, much more likely to have the kinds of qualifications and skills that employers are looking for. I think that we would all say that the apprenticeship programme is a flagship and it's very, very good. In fact, I know people in Germany who look at our apprenticeship programme and go, that's actually quite good.

Robert: Really?

Rebecca: Yes, absolutely.

Robert: It's exciting.

Rebecca: It is exciting. It's really exciting. It's not perfect. Any education system is never perfect. Yes. But we have some wonderful apprenticeships. Employers have been involved from start to finish designing them. And of course, people on apprenticeships work four days a week and they're in the classroom one day a week. And so they're getting that work experience and earning money. While they're doing their apprenticeships. So apprenticeships are a huge shift and they will and already do actually start offering alternatives to some people who would have gone to university. T-levels are the other one, much newer qualification. Only been going a couple or three years.

There will be eventually 24 T levels, they're all technical and vocational. Each T level is equivalent to three A levels. So the kind of people who do T levels, who opt to take a T level, would have done A levels. Again, there's work placement and employer involvement, but it's the other way around from and one day with an employer. And actually, because some employers find that quite challenging, you can take that work placement piece as a single set of time. The T levels can lead to employment or to university or to an Institute of Technology to do a higher technical qualification, which gives people a bit more option, a few more choices about what path they might take.

Robert: Can you share, because I think that's really interesting and I'll confess that I probably like many people have heard about T-levels and I don't really know what type of skill you come out with with a T. So if you've got an example you can share, you said there's going to be one of 24, but if you've got an example of a T level that you're excited about or that you think this is the kind of T level that actually employers should be thinking about.

Rebecca: Without going into a massive amount of detail, the digital T-level is a really great example. Yeah, because what you're doing is you are getting some academic, the academic side of things, but you're also getting the hands-on practical experience. And the T-level students I've met and talked to and seen actually doing some of their stuff, there's a lot of peer learning going on and there's a lot of practical activity, which I think it just brings the subject much more alive than the classic kind of academic way of studying. Working in groups, working in teams, learning how to manage projects together is a really important part of that journey. And so those are the people.

And when you think about the digital agenda obviously, there are some really important jobs that require you to be a technical coder or have technical capability. Might be putting together bits of hardware and software to create a computer system. But the really brilliant thing about the digital world is that there are so many other jobs. And you don't have to be technical to be able to be part of the digital transformation world. I'm not, and I've had 40 years, and it's amazing. It's such a brilliant place to work. And I think that's the kind of vision that you can start to see when you're looking at the digital T-level.

Robert: I love that and thank you for sharing that because I think it highlights we've got two challenges here. One is I don't think probably enough employers, particularly when you move beyond the big enterprise ones like Deloitte, know enough about what a T-level delivers for them on that. And then equally, I think you've got our education system and culture around, oh, well, if you're going to do a digital T-level, then you've got to be a programmer as opposed to, no there's so many things as you just so well articulated that you can do in the digital economy that don't involve programming, but still involve, could be a creative element to it, a digital capability, but not necessarily pure coding.

Rebecca: Now, it does turn out that, you know, quite a lot of people that go into digital do have some sort of affinity with STEM and have to be a coder.

Robert: So I'd like, so I think, you know, that's, that's, it's so interesting that that's one of the challenges, you know, that we have and thank you for sharing about the T levels because I do think that's more that we need to help people understand.

And it comes back to this point about you were sharing earlier, and I would love to give maybe a bit more about this, that you were at a lunch where there's a utility company talking about the thousands of jobs that they've got, and they just can't find it, the people to do that. And maybe you could just sort of share that story a bit, because I think it highlights that there is talent out there, but actually at the moment we're just saying, we need to go and find people who've got the skills as opposed to, oh, actually maybe there's an untapped pool of talent where actually we could train up on the skills or even develop skills.

Rebecca: So we have massive skill deficits in different areas. One of the numbers that was quoted at the lunch that you mentioned was that the water companies need, I think it's just one water company, it needs 30,000 people over the next 10 to 15 years only to manage leaks and sewage. It's huge. And that's new people. That isn't people that they've already got, that's actually what we need in terms of high-voltage electricians or specialist welders. We need thousands and thousands of these kinds of people. If you think about just the one tiny area of building wind turbines, you know, and the specialist skills that go into the assembly and then the maintenance. We just have we have a massive deficit and they were actually talking about welders yesterday. I can't remember the precise numbers, but let's say we have 10,000 specialist welders in the country and we need 30,000.

The other guy who was at the lunch was a recruiter and he was saying, oh yeah, we're on the phone to the 10,000 every three or four months because there are so many openings. And then you talk about construction more than 220,000 vacancies in construction. And these, again, it's a bit like digital. People think when you talk about welding or electricians or construction, they have a kind of view of what that means. And it's not really right. All the sectors have changed, so the jobs have changed, but also there are nuances within those jobs.

So for example, we talked a bit about fusion. And you can imagine a world where it might be possible for a specialist electrician to install an electronic vehicle charging point. And you might think, and I might think, that you could take an electrician that was used to doing another specialist electrical work in a different sector and they could do that job. But that actually turns out not to be the case. It's not because necessarily of their capability. They could probably, in many cases, have 80% of what they need and 20% could be trained. But the way that we've siloed our professions and the way that we silo the certifications and accreditations means that actually, it's quite difficult to move people from one job to another.

And if we think about major infrastructure projects around the UK, we could see a scenario which would say, okay, we're building Hinckley, but in due course, that programme that the people they need will lessen. So why don't we look at, well, where else do we have really big infrastructure projects in the South or the Southwest that we could think about building a pipeline for those people earlier? And if they've got 80% of what's needed for the new project, let's get them trained on the 20% so we can move them on. But we don't think about, I mean, that's not the way we think in the UK.

We don't think about how to manage an industrial strategy around major infrastructure projects, and then what the pipeline might look like for resources, and then how you might resource that. That's not the way we think. We're much more likely to leave it as a kind of bottom-up market force. But at the end of the day, I don't think that's working.

Robert: Yes, totally agree with you. And I'd like to explore a bit further that point that you started with on this, that you've got organisations that know that they're going to need 30,000 new jobs, there are 10,000 people who can fit that. And so the recruiters are loving it. And you've made this point before, that the amount of money that we spend on recruitment costs, chasing the 10,000 to pay them more money in order to move. And yet that hasn't changed the dial in terms of we still got 20,000 vacancies.

And I think what you've really highlighted there is that if we're going to solve this and you make a great point about transferable skills, we've got to think about how we recruit differently. And it has to be looking at those transferable skills. And so one of the things that I've shared with you before, and you know that I'm passionate about scrapping the CV, because I just think the way we have just a, it's like a comfort blanket.

It’s culturally embedded way that we think about how we find talent. And it starts with a job description that lists the hard skills that somebody's going to need with an occasional little thing at the bottom of the job description that says communication skills or written skills, excellent written skills required. So the transferable ones are almost an afterthought.

And so I think that we've got to really tackle this idea of the job description and the CV as being the way that we go out to market to find talent rather than the current approach, which is, well, just let's just ask somebody with the skills that we've listed there. Is that your experience too? Is it not just me that is sitting here thinking that the CV is a real barrier to how we find talent?

Rebecca: So I think that's so interesting. I've had a fascinating conversation recently with a digital company who are, who have scrapped the CV and they're hiring for potential and they, they assess people really hard.

They do a really hard assessment but they get people who are much more likely to be successful in their environment. I'm working with four young people at the moment, all of whom I think are incredibly talented, high potential, loyal, confident, articulate, and ambitious. They just all, unfortunately for them, would like to move sector. It should be unfortunate. It shouldn't be. It should be amazing. But they are all finding it incredibly difficult. And we're talking about not just a few months, but over a year in all four cases where people have they've been trying to move and not even necessarily completely different sector, it could be contiguous sector. And none of them are getting anywhere because of this issue of how the CV is received in the company and how it's read and how it's just discarded if it doesn't have exactly the right match of the words, skills and experiences that they're looking for.

I have worried for decades that… there was an old statistic that used to come up a lot that 80% of all jobs were got through some kind of personal contact. For me, I think that's terrible because how do you get social mobility? How do you get diversity? How do you truly get the kind of talent and potential that you need as an employer if, in fact, the vast majority of the people you're hiring are through some sort of contact?

Robert: Yes. Or some special education or experience.

Rebecca: So we've got to change that. We've got to change that. Employers do need to find ways of hiring to potential, find ways past their HR processes, find ways into the market to meet people and sit down and talk to them, and understand what they have to offer. So that's one of the reasons I'm a big fan of apprenticeships and T-levels for early careers. Yes. But I'm also a big, so the government have got thousands of skills boot camps running now. These are short courses, up to 16 weeks, but they're guaranteed with an interview at the end. So you are going to have an opportunity to have a conversation. These four people I'm talking about, they really don't even get that opportunity to be able to sit across the tables with somebody and talk about what they can do.

So Skills Bootcamp is for many thousands of people a great way of looking at, well here are my skills, this is what I could do, I'll go and do this course, I'll get an interview at the end of it and maybe I'll be able to move on. It's not enough, but it's a start.

Robert: A very important start and I think part of the Scrap the CV campaign is getting employers to think that actually, the way that we need to find talent has to be different from the way that we have done it in the past. Do you worry a bit, because I hear there is a lot of great work that is going on. The Government has really been supporting apprenticeships, T-levels, skills boot camps, so there is a huge amount that is going on there, and yet we still have this enormous amount of vacancies.

Do you worry a bit about the AI and Gen AI excitement and drive that is pushing through further automation and efficiency, that that could actually make this situation worse if we're just looking at word matching, because you were saying, well, you've just got to get the skills, get people in front of people. But the danger is that AI could be going into organisations and just automating an already not fit for purpose recruitment process.

Rebecca: You know, the irony here is that AI could be massively helpful. Yes. If you organised it so that your AI systems were going out looking for the kind of potential you needed, as opposed to very, very specific skills to fill vacancy you have today, I think AI could be massively helpful and probably will be in the future. I mean, AI will come anyway. It's a question of how we choose to deploy it.

I think that if we use it to promote and augment the kinds of recruitment systems we already have today, we get what we asked for, which will be not very good. However, it's a possible tool where you could go out and look for people with all kinds of capabilities that you know you need and no, they might not be a hundred per cent match but yes, they might be an amazing employee.

While I'm on the subject of employees. Can we talk a bit about upskilling?

Robert: Let's talk about upskilling and whether that is an appropriate term, because you're right, the talent could be found in both externally and internally, and actually there's a great opportunity for people within organisations to acquire new skills.

Rebecca: So I've been really fortunate in my life. I've worked for two great employers who have invested huge amounts of money in their employees throughout all of their careers. And honestly, if I was still doing the same that I was doing in the early 1980s… I wouldn't have a job. Everybody has to evolve, everybody has to change and part of the interest and excitement of your career is being able to do that. I worry that in the UK we spend far too much money recruiting people and some of that money could actually be better invested for employers in taking their existing employees and working out how to make them the best they can be.

And part of that might be to do with the way our labour market runs, you know, there's kind of flexibilities that we think we have, as opposed to other countries. But I'm not absolutely sure and nor of the government. And so at the moment, we're really interested in, in trying to find out what's going on with upskilling employees.

The data we have available which may well not be perfect, but the data we have available suggests that the UK spends about half the average of other European countries on upskilling its own employees. Significantly less. Really, really significant. Now we don't know how good our data is and we don't know if this is true and we'd like to find out. So we don't know whether people are saying actually it's too difficult or complicated to keep evolving and training people. So we'll let them leave when their skills become obsolete and we'll go out to the market and recruit more in. And or whether even CFOs might have a view that recruitment is like a tap that you can turn on and turn off. And of course, it isn't anybody who's done recruitment knows it's not like that. If you turn it off, it's very, very hard to turn it back on again.

But I have a suspicion, and I'd really like to know more about this, I have a suspicion that quite a lot of companies are doing quite a lot in this area. If you ask an employer, are your employees different now to where they were 10 years ago? They go, well, of course they are. And then I say, well, how do you know? How do you measure that? How do you track that? How do you report that? And they go, probably not very well.

Robert: What you're leading to there, and there's a huge trend around this, is the skills-led organisation. And I was recently talking to the chief people partner at a leading professional services firm about that too. And they've invested a lot in understanding what skills they've got and what skills they're going to need. And I think one of the interesting things for me around this is that everybody's running around at the moment trying to work out what skills they've got, what skills they're going to need and therefore, partly how do they need to provide some training around that and then what they might need to go out to the external market for.

And I think it comes back to the potential piece around this, which is if you're going to hire for potential, you've got to have a very, very good system for training for potential too. And that's not just for external, that is for internal as well. And I do, certainly from the conversations I had with Arctic Shores clients, feel that there's a lot of work and money that's gone into making it easier for employees to get access to learning tools to be able to acquire new skills. One of the things I thought was really interesting around this I heard recently was that the typical digital skill that we pick up now may have a lifespan of three years.

So actually, every organisation is starting to think, well, maybe what we have, what we bring in and what we have in the office is just about potential. And therefore, it has to be constantly learning and training our staff to enable them to pick up new skills on this.

And so for me it does come back to potential again and rather than thinking about, I think it's quite interesting your point about upskilling and skills crisis and you don't hear about people talking about well how do we develop potential, how do we find potential. And so there's an interesting thing I'd like to get you all to take on language around this too because rather than you and I talk a lot about potential. You've mentioned a few times, I've mentioned a few times. And yet the language everybody's using is around skills.

And how do we upskill, how do we find skills, rather than actually maybe we should just be talking about potential a lot more, both potential in the organisation and potential out there. And if we really thought about it in that way, we might be using the huge transformation that we're going through now as a means of redefining how we develop people rather than just simply, oh, we've got a skills crisis, how do we find a skill?

Rebecca: So it's really interesting. I think you can get kind of a bit hung up on different words and languages constantly evolving anyway. My kind of my personal view on this is that most people need some sort of foundational core of capability. You could call it a set of skills.

Everybody needs other capabilities built on the top of that. Right. Now when you go to a further education college, which I really hope you will, because they're amazing places, they often talk about universal skills or foundational skills. And these are the kind of core capabilities that everybody needs to be a successful employee. You know, being able to work autonomously or in a team. Be a self-starter, be inquisitive, have communication skills, probably some sort of finance capability along the way, bit of digital, you know. So there's a kind of round mix of stuff. And most of our further education colleges are trying to equip their learners with those skills.

When you turn to employers, what I think is really interesting is the a lot of the large employers that I talk to now have these really excellent educational platforms that they've installed in their businesses with a plethora of what looks like extremely high quality educational material available to employees that they can take on in a self-guided way.

My questions here are, how are you ensuring that that plethora of self-guided materials is really tightly coupled with your own strategy? And your own strategy, which obviously is tightly coupled with the country or the world strategy, depending on your business. And then how are you linking that back to an individual in terms of their own personal journey? Is it linked back to their appraisal? Is it linked in some way to a continual professional development plan that some looking at, discussing with them and talking to them about and then is how is it being reported. I'm always quite interested in outcomes and how do you know that you're getting the outcomes you're looking for and how are you measuring it and then from my point of view how are you reporting that out to the government so that we know what you're doing and maybe get more accurate data.

Robert: I think that's a really, really interesting point. And I love your bit around foundational skills and thinking about what are just the core things that will enable somebody to pick up new hard skills. But you've got to have the foundational skills in there. And that's something that, Arctic Shore's particularly passionate about. Something that we talk about as skills enabler around that. And that's helping people think about that.

I think you highlighted for me almost three really important pillars for people there and I hadn't really thought about it until you articulated it in that way, which is what are the foundational skills, how do we personalise it then for the individual when they're in the organisation or when they're coming into the organisation, and then how do we capture the outputs from that. And actually it could be as simple as that, rather than we have to go through a massive skills transformation programme and spend lots of money about working out what skills we've got, what skills we're going to need and turning it into a big three year project, rather than actually just simply looking at it.

These are the principles, what are the foundations, how do we personalise it and enable it for somebody and then how do we measure whether that has actually delivered the outcomes we hoped years to do any of these projects.

Rebecca: So for employers, yeah, I think the really important things are get involved with your local community, find out what people want and are able to do, talk to local providers, go to your FE college and work out what they're doing and whether they can start providing you with the kinds of people that you need.

But I also think there's another aspect of collaboration that we all need to do, but particularly employers, which is to talk to other employers in your sector and work out if there's a big skills shortage, can you work together? Is it possible to work together to come up with, I don't know, your own skills bootcamp or your own industry-based training program that you can all buy into and all benefit from? Because I don't, I think we think often employers are just competitive, but of course they're not. And collaboration is absolutely key. And I do think collaboration between education employers going forward at a regional and local level is going to be one of the really most important keys to unlock growth in this country.

Robert: I think that's two excellent pieces of advice. Again, iterate for all those listeners on this podcast to think about that. First of all, which I promise and commit to going to go and find my local one near London Bridge on that one. I have visited a few in the past, actually one in Bristol, Newham as well, Further Education, which I think you're absolutely right, they are amazing, a lot better than many people have and they've transformed hugely in terms of the skills they give people. So I think go out there and visit them and find where your local further education college is. I also really like your point about collaborating with other people in the sector.

We talked in the past about the Northwest Talent Tech Consortium that the PWC, Siemens, and others have led in Manchester, where they've gone out collaboratively into the schools to talk about the sort of skills that they need, encouraging people from different backgrounds, different educational capabilities to think about digital jobs in a different way. And that's a great two starting points to do that.

So Rebecca, wonderful thoughts and advice. Thank you so much for coming along to the podcast and good luck in your wonderful sort of programme and support for the Department of Education in Skills Reform because it's something that's going to make a big difference to the country.

Read Next

Sign up for our newsletter to be notified as soon as our next research piece drops.

Join over 2,000 disruptive TA leaders and get insights into the latest trends turning TA on its head in your inbox, every week

Sign up for our newsletter to be notified as soon as our next research piece drops.

Join over 2,000 disruptive TA leaders and get insights into the latest trends turning TA on its head in your inbox, every week